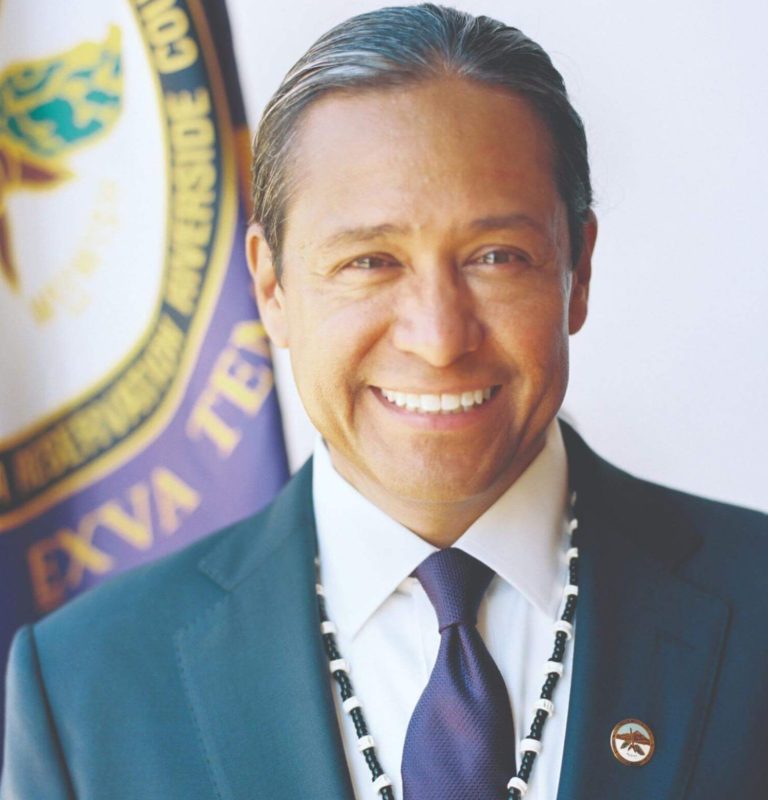

By Mark Macarro

Tribal Chairman, Pechanga Band of Indians

Vice President, National Congress of American Indians

Recently, I was asked to comment on the current political landscape, both in and out of Indian country: the history, strides, and future of what may help in achieving current legislation that will further the recognition of Indian communities in larger bodies of government. While the frame of the question posits an Indian Country paradigm with an in and an out, the premise is anachronistic. Indian country is, and the United States is still learning it must meet Tribal nations and Indian people where they are.

In November 1998, by a vote of 63% to 37%, Californians overwhelmingly supported the Tribes’ ballot referendum: Proposition 5. The Indian Gaming and Tribal Self-Reliance initiative would have mandated that Tribal-state compacts be negotiated and promulgated under the parameters of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA). When the measure was struck down on a technicality, the Tribes returned in the November 2000 election with Proposition 1A, and again won overwhelmingly with an increased margin of 65% to 35%.

In the wake of that resounding victory, one of California’s then-power players assembled 30 of us, Tribal leaders, into his Capitol office. While we assumed the impromptu meeting would be congratulatory in nature, and it was, he proceeded to impart his unsolicited advice to us upstart political neophytes. “Congratulations to you all on your amazing victory, enjoy and savor the moment,” he orated, “political power is never given, it is always taken—and those who’ve had it taken from them will want it back.”

A cautionary admonishment to be sure. This seasoned politico’s advice was insightful for confirming how the political game is played in America: individual players in the system are Machiavellian, and when a win is scored, it’s a zero-sum result. Political power and the accumulation, thereof, are a goal unto itself. Often someone’s observations say as much about themselves as the thing they’re trying to comment on. In this case, the transference of personal values to tribal leadership’s motivations could not have been more wrong.

For Indian people working in politics, government, education, entertainment, science, and a multitude of allied fields and endeavors, the betterment of our communities and our people is our motivation. Our catalysts are decades, and centuries of injustice, inequity, and diminishment. For so long, so many have done so much to make us disappear. Federal policy vis-à-vis Indian country since the 1850s alone is a shameful testament to this. Despite it all, we are still here. We have persevered and have a legacy of resilience—both of which we are imbued with from so many of our collective ancestral and cultural teachings.

When called upon to serve one’s people, a question is often asked: what will you do when you have the chance to serve? We have seen the answer play out throughout Indian Country where many have worked to right the scales of justice, to bring equity to our tribal communities, establish parity between Tribal governments and flex our existence—not as an exercise of strength, but as a means of moving across the continuum from survival to resilience.

Throughout my past 30 years of service on the Pechanga Tribal Council, and as the incumbent Tribal Chairman for the last 27 years, I have seen Indian Country grow to be more empowered with each decade, becoming increasingly proactive in exercising and asserting Tribal sovereignty; Significant successful strides in applying jurisdictional governmental powers throughout a multitude of subject-matter arenas have been accomplished. The Oliphant gains made in the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), and further expanded in VAWA 2022, is but one example.

Along the way, a strengthening of Indigenous identity has manifested—with a strong resistance and push-back to others’ attempts to appropriate, to mascot, and to define who and what we are. The progress through this period has been made by our own Indian people—making significant inroads with their education, experience, and the vision of our forebears to create a world reflective of who we are. There is such a powerful sense of obligation to be true to those who came before.

Tribal nations need to continue this trajectory of successful gains. A critical way to ensure this happens is to be at the table where Tribal priorities are discussed and considered; To be in the room where it happens. A hallmark of this strengthening is that empowerment has been on our own. The United States Department of the Interior Secretary, Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), became emblematic of this with her appointment by President Biden to his Cabinet. Secretary Haaland’s successful appointment was on the relative heels of having been elected, together with Rep. Sharice Davids (Ho-Chunk), as the first Native American women elected to Congress. Sunshine Sykes (Navajo), appointed by California Gov. Jerry Brown in 2013 to the State’s Superior Court, is now confirmed to serve as a judge on the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, the first Native American to ever join the federal bench in the State of California. Minnesota’s Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan (White Earth Ojibwe) is the highest-ranking Native American elected official in the U.S.

It is a remarkable period of accomplishment we find ourselves in. Political and legal success in recent years includes the Indian Health Care Improvement Act of 2010, the Supreme Court’s McGirt decision, the unprecedented funding to Tribal governments via the Coronavirus Relief Funding/CARES Act, the American Recovery Plan Act, and the impacts of the Native vote on no less than the election of the president. Many Tribes have been able to have lands returned to their jurisdictional control, either through federal land transfers or from real-estate purchases. Is it an insult to injury that a Tribe should have to buy back land which was once theirs? Perhaps, a question for another place. How many acres have been returned and what number of acres indicates success? Suffice it to say, many in Tribal leadership are pleased when such lands are available for land back in the first place. My view? A win is earned when there is a Tribe, still, to receive land back and land is available to be returned.

The Native presence in the world of the media, entertainment, and the arts has seen a tremendous increase in visibility with its practitioners pushing boundaries further than ever, and insisting on Indigenous content being created, written, acted, crewed, and show-runnered by Indian people. Flagship shows like “Rutherford Falls” and “Reservation Dogs” are leading the way. Other shows with significant Native participation on both sides of the camera include “Yellowstone” and “Resident Alien.” The literary space is framed by three-term U.S. Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo (Muskogee Creek Nation), the 23rd poet laureate, and the first Native American. Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain Chippewa) has earned, not only critical acclaim as an author, novelist, and poet, she was the 2021 Pulitzer Prize winner for fiction for “The Night Watchman.”

Challenges remain and confront many of us. The Brackeen case, that’s currently before the Supreme Court, is the current and most serious threat to the Tribal sovereignty we currently exercise. Some in Congress have voted to diminish the voting rights of significant parts of Indian country—where Tribal populations and land bases are large, but the communities are rural. There remains a chronic and uneven distribution of infrastructure throughout much of Indian country and especially among Alaska Native villages. Communication facilities, broadband capacity, and adequate roads are either non-existent or dilapidated and aging. These items are a few of the essential building blocks necessary to establish a commerce core and build a tribal economy. A deep, unmet housing and adequate health care need remain acute with no long-term solution at hand. Other challenges include the protection of sacred places and no uniform set of laws comprehensively protecting the sacred religious customs and practices of American Indians and Alaska Native people. Tribal nations must tackle multiple threat sources from projects where local, state, and federal governments all can act as lead agencies.

Our Tribal nations, our people, are resolute and have an ancestral understanding of the long game. This gives our leadership the wisdom of perseverance, patience, and the tool of good timing. We apply lessons from our recent histories—many of which did not go so well—we can forge ahead with added resources in our toolbox to level the field of challenge and create the change necessary for our tribal communities. By doing so, we create the parity and respect we deserve. And with patience, sometimes we just get lucky—lucky that our pesky colonizing neighbors, being single-generation oriented, move away. Meanwhile, we are still here.

Read more articles in our latest spring issue of The American Indian Graduate.